Gargliardone I, Gal D, Alves T, Martinez G “Countering Online Hate Speech“, June 20, 2015, pg 13 & 14. Unesco Publishing, http://www.scribd.com/doc/269217679/UNESCO-Countering-Online-Hate-Speech#scribd

The UNESCO published a report “Countering Online Hate Speech” as a part of its UNESCO Series on Internet Freedom. It quotes Dr Andre Oboler, CEO of OHPI, and also mentions our online hate reporting tool FightAgainstHate.com.

Page 13:

Hate speech can stay online for a long time in different formats across multiple platforms, which can be linked repeatedly. As Andre Oboler, the CEO of the Online Hate Prevention Institute, has noted, “The longer the content stays available, the more damage it can inflict on the victims and empower the perpetrators. If you remove the content at an early stage you can limit the exposure. This is just like cleaning litter, it doesn’t stop people from littering but if you do not take care of the problem it just piles up and further exacerbates.”4

Page 40:

Organizations like the USA-based Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the Women, Action and the Media (WAM!), the Australian-based Online Hate Prevention Institute, the Canada-based Sentinel Groups for Genocide Prevention, and the British-based Tell Mama-Measuring Anti- Muslim Attacks have become increasingly invested in combating hate speech online by targeting Internet intermediaries and asking them to take greater responsibility in moderating content, and by trying to raise awareness among users.

Page 41:

Examples of initiatives crowdsourcing requests to take action against specific types of messages include HateBase, promoted by The Sentinel Group for Genocide Prevention and Mobiocracy, Tell Mama’s Islamophobic incidents reporting platform, and the Online Hate Prevention Institute’s Fight Against Hate. These initiatives take combating online hate speech a step further and serve as innovative tools for keeping track of hate speech across social networks and how it is being regulated by different private companies.

In discussing the importance of generating empirical data, the Online Hate Prevention Institute’s CEO, Andre Oboler stated that platforms like these offer the possibility to make requests visible to other registered users allowing them to keep track of when the content is first reported, how many people report it and how long it takes on average to remove it. Through these and other means, these organizations may become part of wider coalitions of actors participating in a debate on the need to balance between freedom of expression and respect for human dignity. This is well illustrated in the example below, where a Facebook page expressing hatred against Aboriginal Australians was eventually taken down by Facebook even if it did not openly infringe its terms of service, but because it was found to be insulting by a broad variety of actors, including civil society and pressure groups, regulators, and individual users.

Pages 42-43:

This discussion section of the report looks at the Aboriginal Memes incidents of 2012 and cites OHPI’s Report “Aboriginal Memes & Online Hate“.

Long-haul campaigning

This case illustrates how a large-scale grassroots controversy surrounding online hate speech can reach concerned organizations and government authorities, which then actively engage in the online debate and pressure private companies to resolve an issue related to hate speech online. In 2012, a Facebook page mocking indigenous Australians called “Aboriginal Memes” caused a local online outcry in the form of an organized flow of content abuse reports, vast media coverage, an online social campaign and an online petition with an open letter demanding that Facebook removes the content. Memes refer in this case to a visual form for conveying short messages through a combination of pictures with inscriptions included in the body of the picture.The vast online support in the struggle against the “Aboriginal Meme” Facebook page was notable across different social media and news platforms, sparking further interest among foreign news channels as well. In response to the media commotion, Facebook released an official statement on the Australian media saying, “We recognize the public concern that controversial meme pages that Australians have created on Facebook have cause. We believe that sharing information, and the openness that results, invites conversation, debate and greater understanding. At the same time, we recognize that some content that is shared may be controversial, offensive or even illegal in some countries.”108 In response to Facebook’s official statement, the Australian Human Rights Commissioner interviewed on public television asserted his disapproval of the controversial page and of the fact that Facebook was operating according the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on a matter that involved both an Australian-based perpetrator and Australian-based victims.109

The online petition was established as a further response to Facebook’s refusal to remove the content by automatically answering several content abuse reports with the statement, “After reviewing your report, we were not able to confirm that the specific page you reported violates Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities”.110 The open letter in the petition explained that it viewed the content as offensive due to repeated attacks against a specific group on racist grounds and demanded that Facebook take action by removing the specific pages in question and other similar pages that are aimed against indigenous Australians. In August 11th, 2012, the founder of the petition, Jacinta O’Keefe, published a note in which she thanked the participants and announced the petition’s victory when she discovered that Facebook had removed the said content and another hateful page targeting indigenous Australians.111 However, the pages had only been removed temporarily for content review and after talks with the Race Discrimination Commissioner and the Institute, Facebook concluded that the content did not violate its terms of services and allowed the pages to continue under the requirement of including the word “controversial” in its title to clearly indicate that the page consisted of controversial content.112

A second content regulation phase came after a Facebook user began targeting online anti-hate activists with personal hate speech attacks due to the “Aboriginal Memes case. Facebook responded by tracing and banning the numerous fake users established by the perpetrator, yet allowed him to keep one account operational. Finally, in a third phase, Facebook prevented access to the debated page within Australia following publically expressed concerns by both the Race Discrimination Commissioner and the Australian Communications and Media Authority. However, the banned Facebook page remains operational and accessible outside of Australia, and continues to spread hateful content posted in other pages that are available in Australia. Some attempts to restrict specific users further disseminating the controversial ‘Aboriginal Memes’ resulted with a 24-hour ban from using Facebook. These measures were criticised as ineffective deterrents (Oboler, 2012).

Page 46-47

The concern of citizenship education with hate speech is twofold: it encompasses the knowledge and skills to identify hate speech, and should enable individuals to counteract messages of hatred. One of its current challenges is adapting its goals and strategies to the digital world, providing not only argumentative but also technological knowledge and skills that a citizen may need to counteract online hate speech.

…

In recent years, those stressing media literacy have begun to address the social significance of the use of technologies, their ethical implications and the civic rights and responsibilities that arise from their use. Today, information literacy cannot avoid issues such as rights to free expression and privacy, critical citizenship and fostering empowerment for political participation (Mossberger et al. 2008). Multiple and complementary literacies become critical.

…

The emergence of new technologies and social media has played an important role in this shift. Individuals have evolved from being only consumers of media messages to producers, creators and curator of information, resulting in new models of participation that interact with traditional ones, like voting or joining a political party. Teaching strategies are changing accordingly, from fostering critical reception of media messages to include empowering the creation of media content (Hoechsmann and Poyntz, 2012). The concept of media and information literacy itself continues to evolve, being augmented by the dynamics of the Internet. It is beginning to embrace issues of identity, ethics and rights in cyberspace (See Paris Declaration)130.Some of these skills can be particularly important when identifying and responding to hate speech online and the present section analyses a series of initiatives aimed both at providing

information and practical tools for Internet users to be active digital citizens. The projects and organisations covered in this type of response are:

- ‘No place for hate’ by Anti-Defamation League (ADL), USA;

- ‘In other words’ project by Provincia di Mantova and the European Commission;

- ‘Facing online hate’ by MediaSmarts, Canada;

- ‘No hate speech movement’ by Youth Department of the Council of Europe, Europe;131

- ‘Online hate’ by the Online Hate Prevention Institute, Australia.

A comparative outlook on all the listed projects and their materials related to hate speech online was conducted. In addition interviews with representatives of the organisations or people responsible for the educational programmes were conducted.

Page 49

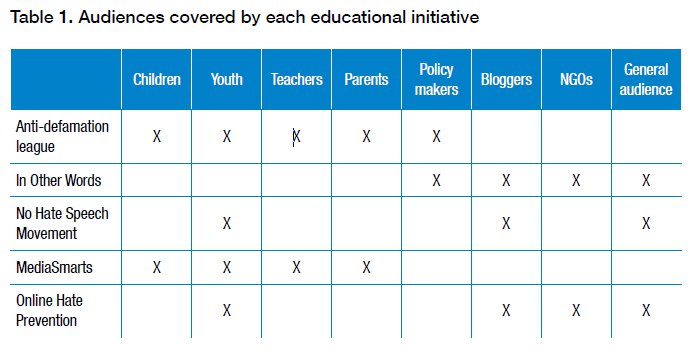

Parents, teachers and the school community also tend to be considered an important audience due to their role in exposing and protecting children from hateful content. Other groups are also targeted include those with the ability to shape the legal and political landscape of hate speech online, including policy makers and NGO’s, and those who can have a large impact in the online community exposing hate speech, especially journalists, bloggers and activists. A summary of the different audiences targeted in the analysed initiatives can be found on Table 1.

On this point we disagree with UNESCO’s assessment in as much as the work of OHPI is also addressed to policy makers. This can be seen in our major reports which include direct recommendations for policy makers. We’ll try to draw this element of our work out a little more clearly in the future. Another audience not listed is technology companies and our work has led to changes in major software platforms like Facebook and YouTube.