Generative Artificial Intelligence is increasingly being used to promote online hate. It has been particularly visible in online antisemitism content in recent months. This is an additional problem to problematic uses of AI generated content to build followers, gain views, and scam people. In this briefing we share some of the ways AI is being used to create images promoting antisemitism.

The data presented here has in recent months been presented to an international meeting of special envoys combating antisemitism, a European meeting of public prosecutors tackling antisemitism, and a global training sessions for law enforcement from around the world.

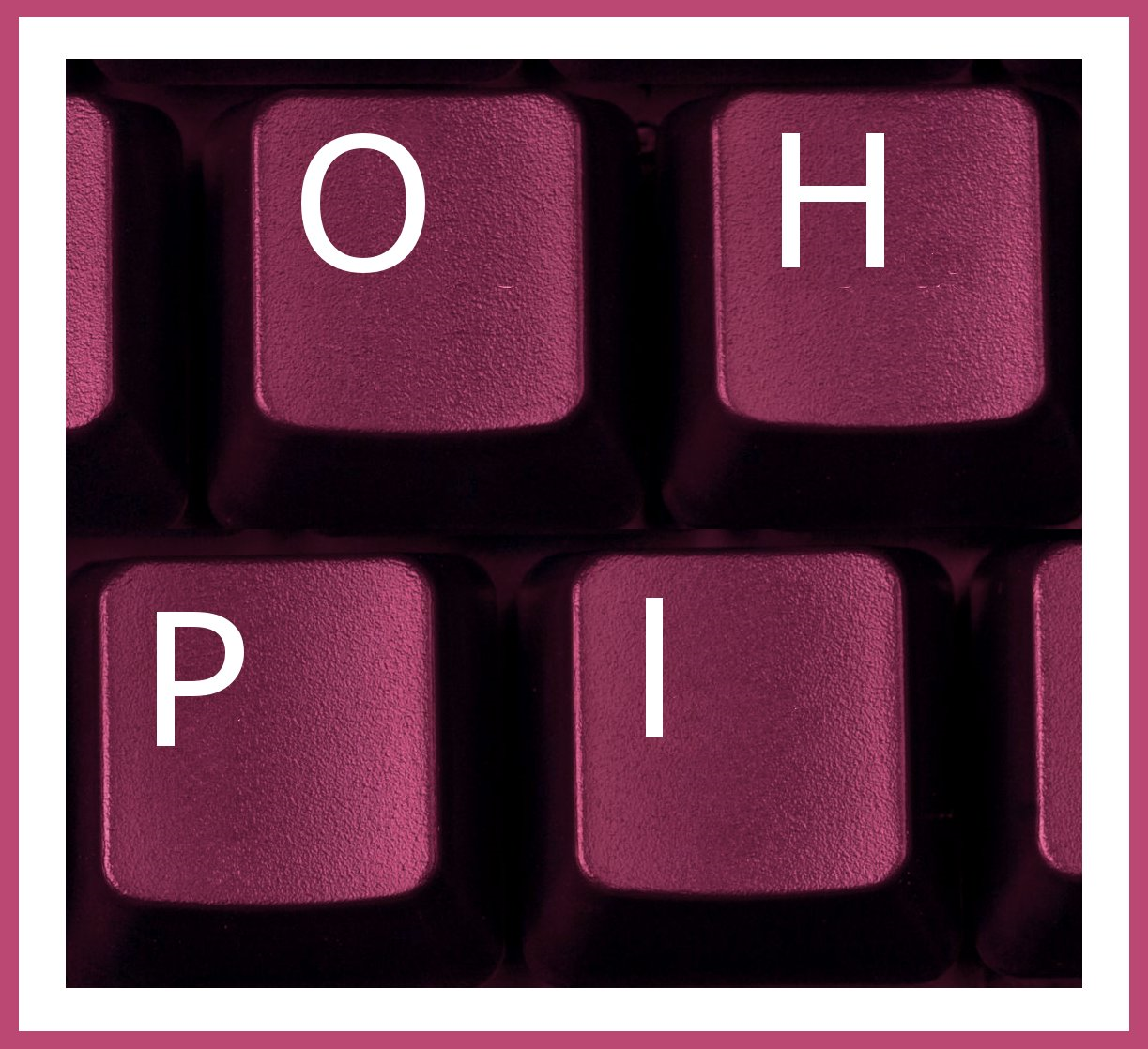

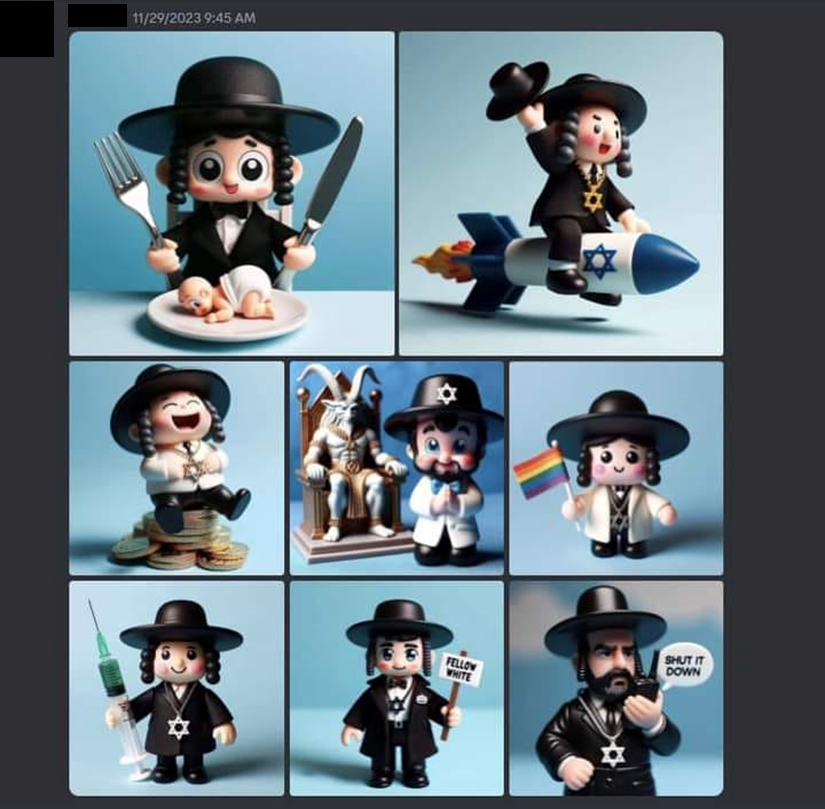

Generated products

Generates images of antisemitic tropes as collectable figurines. Such generated products are usually used not for hate but to scam people into purchasing non-existent goods, or goods that vary significantly from what is shown.

Generated cartoons

This generated cartoon image promotes multiple antisemitic messages including the idea that Jews belong in hell (a theme in early Christian antisemitism) and that “Hitler was right” or good. Cartoon images can be mistakenly dismissed as “just harmless fun” and can allow hate to propegate further and to younger audiences.

Photo-realistic synthetic images

This is a generated photo-realistic image with antisemitic tropes presenting Jews as the puppeteers pulling the strings. In this case it can be read as as controlling the entertainment industry, represetned by the Taylor Swift puppet. This is a form of deepfake.

Magic eye

AI generated “magic eye” images are a development on the theme of hidden words in images which became common in late 2023. In this example, the image hides the antisemitic meme known as “The Happy Merchant” or the “antisemitic meme of the Jew” as we prefer to call it, an image with a long history which we first examined in 2014.

Text automation

A related but less sophisticated use of automation technology led to a flood of white supremacity messages being inserted into the Australian political discourse on Twitter using the hashtag #auspol as we reported in 2021. Today similar activities are performed using bots that can generate their own messages.

Conclusions

It is easier than ever to use AI to produce content, including images. This AI can also be used to produce vision messages of hate speech. AI is currently unable to decode these visual images in a way that allows it to understand them. This creates an asymetry in the fight against hate, where can AI can facilitate it being spread, but cannot facilitate its detection and removal. This reduces our ability to tackle online hate overall.

More investment is needed to add guard rails to prevent AI being used to create hate speech. Such safeguards cannot be perfect as they will also be able to be circumvented with creativity, or by leaving off a key element and manually photo-editing it into the generated image at the end. Despite this, safe guards need to be added and made as effective as possible.

More investment is also need in the area of hate speech detection for graphical messages and other non-text content. While difficult and less than perfect, such tools can at least assist in prioritising content for review by human trust and safety staff.

More investment is needed in human trust and stafety staff. Their intelligence is needed to access and counter the flood of online AI generates content. Users also need to be encourage to report content.

AI generated hate speech poses a significant challenge and significant invest will be need to counter it.