This page has been prepared to support the delivery of an online lecture we are providing for the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne.

For a long time Holocaust denial was limited to discredited academics and fringe groups. However, the Internet allowed Holocaust denial, glorification of Nazism and antisemitism to reach mainstream audiences in increasing numbers. This has allowed the discourse of Holocaust denial and distortion to flourish.

Like other forms of antisemitism, the messages of Holocaust denial are morphing and changing as they spread through social media. Holocaust denial on social media can involve outright denial of the fact that the Holocaust occurred, claims that the number of Jews killed is grossly exaggerated, or content mocking the victims of the Holocaust and glorifying Hitler and the Nazis.

Governments and terrorist groups also use Holocaust denial themes in their propaganda. The Iranian government ran cartoon competitions on the theme of Holocaust denial in 2005 and 2016 which attracted entries from around the world, including Australia. These competitions generated a spike in new content which continues to pollute social media today. During the Israel / Hamas war “Operation Protective Edge” in 2014 a specially created Hamas social media guide encouraged supporters to engage in Holocaust distortion and to liken Israel’s action in Gaza to the Holocaust. This war propaganda persists

We’ve also seen the emergence of what French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy called “Modern Antisemitism”, a phenomena which encourages hatred against Jews by suggesting that they demand special privileges based on a lie. Lévy explains Modern Antisemitism as saying, “The Jews are all the more detestable because they are believed to base their beloved Israel on imaginary suffering, or suffering that at the very least has been outrageously exaggerated. This is the shabby and infamous denial of the Holocaust”.

Glorification of Nazism is also a staple of 4Chan’s politically incorrect forum (known as “/pol/”), the place that radicalised the Christchurch, Poway, El Paso and Halle attackers who carried out attacks in 2019. The spread of these ideas has led to the creation of modern Neo-Nazi youth groups, including in Australia, and posters with swastikas and extreme expressions of antisemitism have in recent years appeared all over Australia.

There have also been growing efforts to tackle antisemitism and Holocaust denial at the international level. In May 2016 the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), an inter-governmental body then with 31 member countries, passed its Working Definition of Antisemitism. The definition gives as two examples of antisemitism in relation to the Holocaust: “Denying the fact, scope, mechanisms (e.g. gas chambers) or intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of National Socialist Germany and its supporters and accomplices during World War II (the Holocaust)” and “accusing the Jews as a people, or Israel as a state, of inventing or exaggerating the Holocaust”. The IHRA definition has since been widely adopted around the world. In Australia it has been adopted by the National Union of Students. A different IHRA definition focused on Holocaust denial and distortion is also gaining traction as the antisemitism definition and awareness of IHRA spreads.

There are increase efforts to monitor and document Holocaust denial online. In January 2016 a breakdown of data collected by the Online Hate Prevention Institute, released through the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s Global Forum for Combating Antisemitism, showed that Holocaust denial content was more prevalent on YouTube than on other social media platforms. The YouTube content included supposed documentaries making dubious claims, clips of speeches and entire talks by infamous Holocaust deniers as well as videos people posted of themselves denying the Holocaust. Many videos carried an air of faux-professionalism, making it easier for a layperson to accept the conspiracy theories without verification. In fact, most people do not have tools or the knowledge to separate facts from assertions, and are depend on independent sources – respected media and journals – to make that distinction for them. The Internet, however, has no filter and content mocking the Holocaust by ways of cruel memes, cartoons and jokes can be seen across the largest social media platforms: YouTube, Facebook and Twitter. Thankfully since 2019 YouTube has been taking action against Holocaust denial.

A 2018 report by the World Jewish Congress into antisemitism in social media found that the number of Holocaust denial content had doubled compared to two years earlier. Encouragingly, while the numbers were rising on Twitter and blogs, they dropped on Facebook and YouTube.

Efforts against Holocaust denial are increasingly focused on the online sphere. At an IHRA plenary in June 2017 Honourary Chair, Prof. Yehuda Bauer told the plenary session that “One of the greatest problem is hate speech on the internet… [with] new technologies hate speech can be spread and is being spread… What we are facing is a vast flood of hatred including antisemitism and Holocaust denial… we cannot keep quiet, we cannot education, remember, research when there is hatred all over the place.”

In response to multiple terrorist attacks in 2019, including the one in Christchurch, and building on momentum that has been growing since the deadly “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017, mainstream social media platforms are doing a lot more to prevent their platforms being used by neo-Nazi white supremacists. The response is not perfect and some neo-Nazi content remains on the mainstream platforms, and new content is still added, but most Holocaust denial and neo-Nazism has now migrated onto smaller platforms, sometime platforms that are dedicated to such communities.

Through the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift of extreme antisemitism including Holocaust denial and distortion away from mainstream platforms and to dedicated platforms has been accelerated. Dedicated resources and technical expertise is needed to monitor and respond. The threat may be less visible to most people, but it is growing rather than shrinking. Holocaust denial is part of a pipeline into radicalisation and extremism. We need to become more aware of the threat and we need both the public and government to invest seriously in tackling it. Holocaust education is important, as is bystander training, but these measures alone are not a complete solution. We also need to monitor and tackle the threat head on, and as a society we need to invest in making that happen.

Selected Readings

Andre Oboler, “Facebook, Holocaust Denial, and Anti-Semitism 2.0”, JCPA, 2009. This articles provides the background to Facebook’s position against banning Holocaust denial.

“YouTube strengthens response to hate“, OHPI, 6 June 2019. This briefing from OHPI discusses YouTube’s move to ban Holocaust denial in 2019.

OHPI’s focus area on Holocaust Denial provides articles document our efforts tackling online Holocaust denial, distortion and trivialisation. Including media coverage, we have publicly responded 31 times since 2013 specifically on Holocaust related issues. Work also happens in private.

IHRA Working Definition of Holocaust Denial and Distortion. This is a separate definition to the more well known IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism.

Andre Oboler, William Allington and Patrick Scolyer-Gray, “Hate and Violent Extremism from an Online Sub-Culture: The Yom Kippur Terrorist Attack in Halle, Germany“, December 2019. Particularly sections 3.2.4 and 5.3.

Exercise Material

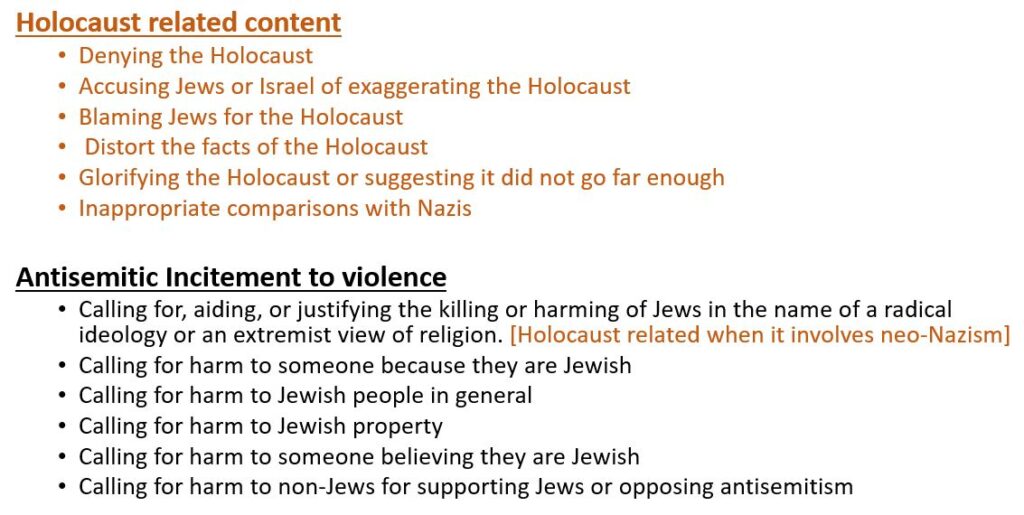

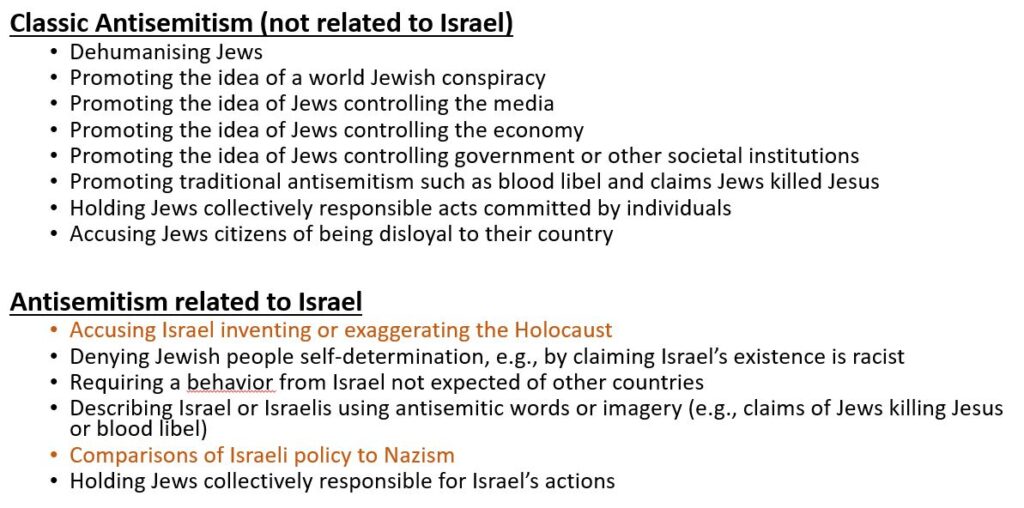

Instructions will be provided in the sessions. The categories we discussed are:

The items you are considering are the following:

Item 1: A YouTube Video (no longer online)

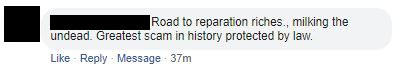

Item 2: A Facebook comment

Item 3: A Facebook comment in response to a Holocaust education post

Item 4: A video on a dedicated antisemitic video hosting site (online now)

Item 5: A Facebook comment in response to a Holocaust memorial day post

Item 6: An Internet meme

Item 7: A comment on Facebook

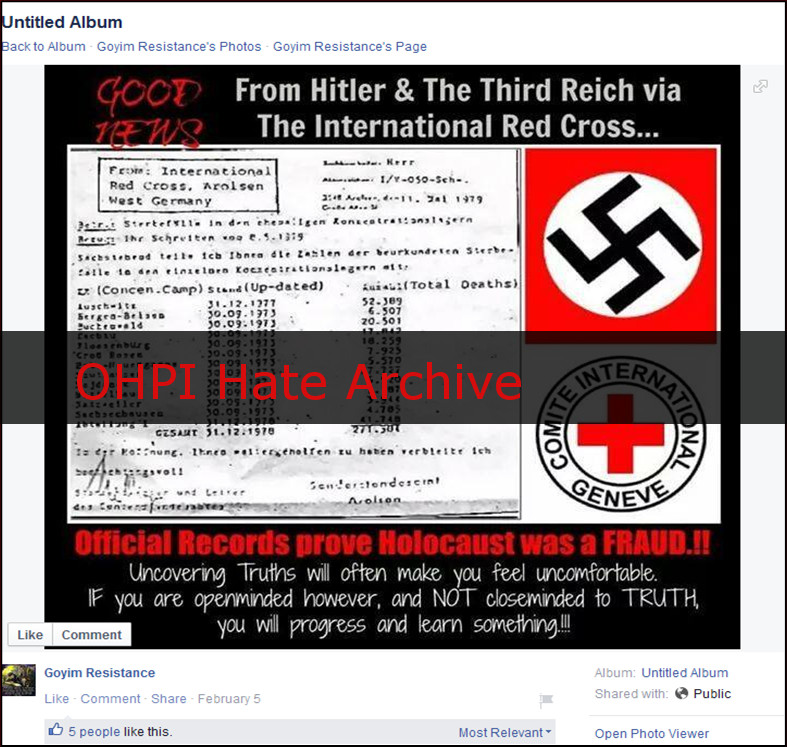

Item 8: An image on Facebook (no longer online)

Item 9: An image from Facebook (still online)

Item 10: A tweet